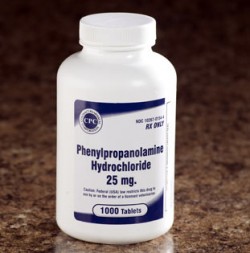

Phenylpropanolamine is a drug that has several uses in over-the-counter drugs, prescription drugs, and is a key ingredient in some illicit drug recipes. Most commonly Phenylpropanolamine is found in nasal decongestants, both OTC and prescription strength, and as an ingredient that helps suppress appetites in weight loss drugs found in over-the-counter formulations.

Phenylpropanolamine helps to relieve sinus congestion, and stuffy noses and also helps curb appetites, but is also an integral ingredient used in the production of the illegal drug methamphetamine. Despite having been prescribed and effectively used for many years, evidence of harmful side effects have caused the DEA and FDA to issue statements and amend the ease with which one can procure phenylpropanolamine in the United States of America.

Yale University Study of Phenylpropanolamine

On May 11, 2000, FDA received results of a study conducted by scientists at Yale University School of Medicine that showed the risk of hemorrhagic stroke (bleeding of the brain) to be increased by people who were using medications containing phenylpropanolamine. Although phenylpropanolamine has been successfully used for a long time, and the number of people taking the drug that have had strokes is small, the Yale study facilitated evidence confirming that the number of people having strokes while taking drugs containing phenylpropanolamine was greater than the number of people that suffered strokes and were not using products with phenylpropanolamine on the ingredient list.

PPA may carry a risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

The risk of hemorrhagic stroke is very low, but the FDA has substantial concerns due to the seriousness health risk associated with a stroke and the inability to foresee who might be at risk when using products or prescriptions that have phenylpropanolamine in them. Continued reports to the FDA of hemorrhagic stroke associated with phenylpropanolamine drug use and the results of the Yale study combined have caused the FDA to feel that the scales of benefit and risk have been tipped and that the positive results of the use of phenylpropanolamine have been overtaken by the distinct possibility that the drug may be dangerous for the user’s health. The FDA now recommends that consumers no longer use products containing phenylpropanolamine.

Population groups at higher risk when using products containing phenylpropanolamine seem to have been targeted as female, but there are questions as to whether this is because women seem to be more likely to use products and drugs containing phenylpropanolamine or if they are simply at a higher risk due to physiological differences. The Yale University study showed that the risk of hemorrhagic stroke was found mostly in women; however, men may also be at risk.

*On December 22, 2005 the FDA issued a notice of proposed rulemaking (notice) for over-the-counter (OTC) nasal decongestant and weight control products containing phenylpropanolamine preparations. This proposed rule reclassifies phenylpropanolamine as nonmonograph (Category II) not generally recognized as safe and effective.

The study conducted by scientists at Yale University School of Medicine, issued a report entitled “Phenylpropanolamine & Risk of Hemorrhagic Stroke: Final Report of the Hemorrhagic Stroke Project.” This study reports that taking PPA increases the risk of hemorrhagic stroke (bleeding into the brain or into tissue surrounding the brain). Findings showed that women were more at risk, but did not rule out the possibility for men to suffer the same side effects from phenylpropanolamine. The FDA’s Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee discussed this Yale study along with additional facts about phenylpropanolamine, and determined that evidence of an association between PPA and hemorrhagic stroke is substantiated. The Advisory Committee recommended that phenylpropanolamine be considered unsafe for over-the-counter use.

Public Health Advisory

A public health advisory was issued in November of 2000, by the Food and Drug Administration, requesting that steps to remove phenylpropanolamine from all drug products and a call for companies that produce and distribute these products to halt all marketing in association with products containing PPA (phenylpropanolamine). This advisory had profound effects on the availability and measures needed to obtain many over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription cough and cold medications, decongestants, and in weight loss products that used to be available over the counter. In response to this request made by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), many companies have reformulated these products voluntarily and are continuing to create better products that work just as well, but exclude PPA (phenylpropanolamine).

In the meantime, the FDA has proceeded with its quest to remove PPA from the market by means of following appropriate and necessary regulatory processes. Following the reports of the studies conducted by Yale, and the requests and actions taken by the FDA, the public is continually asking for lists of products containing phenylpropanolamine. However, since companies continue to reformulate their products, the Food and Drug Administration has not been able to maintain a comprehensive, updated list of products that still contain PPA. The FDA believes that the most accurate method for determining the PPA content is for consumers read the labels of OTC drug products to conclude whether or not the product contains phenylpropanolamine.

Recent History of PPA

Up until recent changes in the control of phenylpropanolamine, PPA was a common ingredient in about 100- 150 products, over half of which are available over-the-counter (OTC). The majority of these products were decongestants and cough/cold remedies that were available over-the-counter. However, at least nine OTC diet aids were among those with phenylpropanolamine in their list of ingredients. In 1981, more than 9 million Americans were using OTC diet aids, which made phenylpropanolamine the fifth most used drug in the United States, averaging over $200 million in revenues just in those dietary supplements alone. America seems to be the only country that has faced or discovered serious concerns regarding the use of phenylpropanolamine, therefore the safety of PPA remains controversial.

Most controlled studies indicate minimal side effects when recommended doses are strictly observed, but adverse drug reactions continue to be documented. With adverse effects of phenylpropanolamine recorded as early as 1965, 142 ADRs have been reported in 85 studies conducted over the years, 69% of these in North America. This doesn’t account for the cases that go unrecognized. In patients under 30, females reported about two thirds of all ADRs experienced. 85% of recorded ADRs occurred after consumption of OTC products versus only 15% after prescription drugs. In these studies, the phenylpropanolamine product often contained combination ingredients, or PPA was consumed in conjunction with additional drugs.

Overdose

An overdose of PPA is attributed to about a third of the cases, however after ingestion of recommended dosages, 82% of the ADRs were still considered to be severe. The most frequently noted side effects involved symptoms similar to acute hypertension, accompanied by severe headache as the most common complaint. We have summarized these data in an effort to alert clinicians to the prevalence of usage of PPA products and the potential for adverse effects. Reported: 24 intracranial hemorrhages, 8 seizures, and 8 deaths (resulting from stroke) were associated with phenylpropanolamine ingestion.

Additional Dangers

Other considerations for changing the scheduling of and therefore control of the substance phenylpropanolamine, have been introduced in the recipes used to make certain illicit and otherwise dangerous drugs. For example ephedrine is metabolized into norephedrine, also called phenylpropanolamine or PPA. Norephedrine has been banned as an over-the-counter substance. Ephedrine is similar enough in its structure to amphetamines that it can cause a false positive urine drug screen for amphetamines. In fact, Ephedrine is used sometimes instead of Ecstasy.

Adverse effects of ephedrine include:

- dizziness

- headache

- nausea and vomiting

- restlessness

- insomnia

- memory loss

- muscle injury

- psychosis

- irregular heartbeat and palpitations

- seizures

- heart attacks

- strokes

- death

It is also important to note that adverse effects do not always depend on the dose consumed. Ephedrine’s ability to increase body temperature has caused serious thermogenic effects, such as heat stroke, this effect is intensified by caffeine.

Ephedrine should never be used by someone with/who is:

- diabetes

- an enlarged prostate

- hypertension

- thyroid disease

- taking antidepressant medications

- breast feeding

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has issued a notice for the purpose of informing individuals and businesses handling phenylpropanolamine that this chemical is used in the illicit manufacture of amphetamine. Amphetamine abuse continues to be a major drug problem in the United States. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Wal-Mart have formed a partnership to control large-scale purchases of three key over-the-counter (OTC) products, pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, combined to illegally manufacture methamphetamine and amphetamine.

Methamphetamine quickly became a drug on the rise in the 1990’s. Methamphetamine is a dangerous synthetically manufactured stimulant that results in the same addiction cycle and physiological trauma associated with crack cocaine. It has been referred to as “poor man’s cocaine” because it provides a longer lasting high than cocaine and costs significantly less. Methods of ingestion include injection, smoking, snorting, or taken orally. This versatility has made it increasingly attractive to casual users and young people.